Thomas Spieckermann comes from the Ruhr area in Germany and currently runs the TAK theatre in Liechtenstein. He studied Theatre Studies, Romance Languages and Literature and History at three universities in three countries and later received his doctorate. Through an internship the TAK theatre snapped him up and has not let him go to this day. He was previously employed at seven state and municipal theatres as dramaturge and chief dramaturge. For him, the artists and the scripts of the plays were always the main focus: what and how can the storyline best be told? Projects involving international cooperation have also always been important to him. When you leave behind the image you have of yourself within your own culture, life becomes all the more exciting. Running a theatre as he does now means putting together the theatre’s artistic programme in cooperation with his team and continuously looking for innovative new ways to do things, new contents and new forms. But it also means managing the theatre in terms of personnel and finances, securing its future, and anchoring it in the country. It’s an exciting and challenging job every day. Thomas Spieckermann loves travelling to foreign countries and exploring their cultures. He loves being in nature and he is fascinated my many sciences, particularly astrophysics, elementary particle physics and geosciences. Other interests he has include photography, mountaineering and climbing, books and films and jazz music.

Where and how did you grow up?

I grew up in the 70s in the Ruhr area. It was a turbulent time. The RAF was wreaking havoc right through until the German autumn of 1977. I still remember well the images on TV of the attacks, the hijacking of the Lufthansa plane “Landshut”, and Hanns Martin Schleyer, holding up cardboard plaques to the camera to show the number of days to that point since he had been kidnapped. These were of course distant events which I only saw on TV, but the social climate and public demonstrations were constantly present in my mind in everyday life – demonstrations against the educational system, indeed against everything which represented the status quo. At the same time, structural change was taking place in the Ruhr area, away from mining and towards something else … – what that something else is is still not clear to this day. The mining industry shaped and gave identity to the Ruhr area, and the mining company closures have torn the region apart to this day.

As a child I grew up in a huge conurbation in the middle of a city, in an almost idyllic apartment building with a back garden and a stream running behind it. The whole city quarter looked like this, with a succession of gardens side by side, a path running behind them, and a meandering brook beyond the path. This brook used to be polluted by sewage and it was forbidden to go into the water, but today the water has been treated and it is now clean. In my memory there were only warm summer days and all the children from these conurbations would meet outside to play together every day. TV hardly played a role, and of course, there were no mobile phones at that time. We played football and rode bicycles, and when that all got a bit boring, the bigger adventures would begin. I remember vividly one time when the emergency doctor had to pick me up when I stepped on a nail on an industrial wasteland, and I received an succession of tetanus injections as insurance as the doctor didn’t know whether or not I had already been vaccinated.

Could you describe your professional background?

After my high school graduation I was supposed to do an apprenticeship in a bank, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I really wanted to study instead. I thought I ought to do something solid, something with good job prospects, so I enrolled to study physics, but didn’t work out at all of course. Then the chance to study drama came up and I soon realised that I was now going to do something that my heart was set on. Some relatives scorned my choice of career path and predicted unemployment, but my parents supported me. I did three semesters in Bochum, two semesters in Vienna, before then moving on to study both in Spain and in London. Things got better and better. In Vienna I went to the theatre every day, sometimes twice a day. I was in my element. One time I remember going to watch “Heldenplatz” by Thomas Bernhardt, which was directed at that time by Claus Peymann. The play was a mega-scandal in the theatre world. During an audience discussion after the performance I was sitting next to a man who suddenly stood up to answer a question. It was none other than Thomas Bernhardt himself!

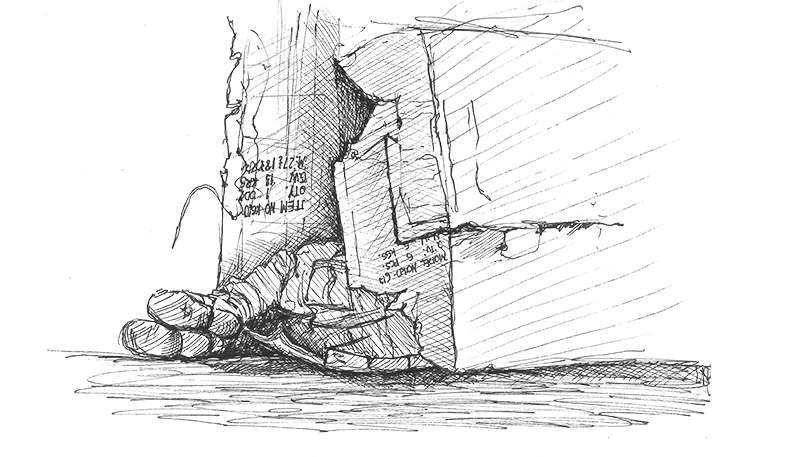

London was great for me too. It was a deeply divided city at that time, with bitter poverty in certain areas as a result of the politics of Thatcherism in the 1980s. From Waterloo Station to Waterloo Bridge you had to walk underneath road bridges under which homeless people had built entire city settlements out of cardboard boxes and had settled down there permanently. Fires burned in empty oil barrels to keep them warm, and on almost every corner in central London someone would ask you plaintively: “Can you spare some change please?”. You were also often physically accosted and sometimes even molested. It was really a harsh city back then, and very different from what it is today. At the same time, there was an incredibly vibrant cultural scene, with backyard theaters, and modern dance in Angel or Camden Town.

After London I came back to Würzburg for private reasons and I was hired by the theatre there. I was really engaged in my work there. The director at that time was a humanist, in the true sense of the word. As an actor he himself still worked with Kurt Hübner and Gustav Gründgens. As a director he was good, even if not extraordinary, but he could open up a whole world to you on a reading rehearsal for a production. It was like you had been granted access to a secret universe – Shakespeare, Chekhov, Goldoni, all at your fingertips. I was deeply impacted by my experiences there and I have stuck with the lessons I learned at that time.

Were there certain events or stations that were formative for your career?

I had a school friend in my senior secondary school years who was very interested in art. In the last two years he had a car with which we went to the theatre almost every day. In the Ruhr area the cities converge almost directly into one and other and every city had its own theatre. So one day we were in Bochum, the next in Dortmund, then in Düsseldorf, then in Mülheim, where the Theater an der Ruhr was a particularly interesting stage. These experiences were certainly formative for me.

In 1989 I went to a non-European country for the first time with another school friend. We had booked a flight to Beijing, and a fellow student who was studying Sinology there wanted to show us the country. We flew there. It was late summer in 1989 and the Tiananmen massacre had just happened a few weeks earlier. When we arrived, we found out that our fellow student had already returned to Europe and we were on our own. We were all at sea. We couldn’t communicate, nobody spoke English. We also didn’t have enough money with us and soon we had to go to the German embassy. Everything felt strange and uneasy. In the supermarkets they only sold kiwi jam, the bike we rented was stolen and at night the police arrested participants in the riots. At Tiananmen Square you could see the bullet holes from June 1989. Public places were closed and the population was traumatised. In the Forbidden City we were alone, the only tourists to be seen far and and wide. When we got to the airport in Beijing we heard that Austria had opened the borders to Hungary. It was a time of dramatic change.

This experience was also formative for me – it kindled my curiosity to experience and to learn more about what life is like for people in other countries and regions of the world.

Has your environment supported you in your career?

My parents and my partner have always supported me, as have some close friends. In any case it’s a small group of people.

Does what you are currently doing fulfil you?

Basically yes. But of course, it’s not the same every day. Many things are unpleasant or annoying and many things have to be repeated over and over again. Some things fail, projects fail, good intentions lead to opposite effects. Perhaps one can say that it is a dynamic environment in constant change. But that also often makes it unpredictable and interesting. I can never respond to new questions with the same answers. I always have to re-assess and re-evaluate the situations. I find that both positive and exciting. And then there is also the art. Sometimes I work on the computer the whole day, then I go over to the performance in the evening, see an actress or a musician and I am moved. A special moment of truth or beauty on stage can completely grab me and that is very fulfilling. Likewise, there are moments in working together during rehearsals or concepts, when a new thought, born in conversation or in the mind, opens a new world. That is also fulfilling for me. However, these moments are few in the flow of time.

Do you think that you yourself have an influence on whether your activities are fulfilling?

The fulfilment is fleeting, but I can have an influence on whether I find my activities meaningful. This is an important prerequisite. I can try to find a job that suits my inclinations and talents, and I can try to carry it out to the best of my ability. The feeling of being meaningfully or even fulfillingly active is not a permanent state, it depends on the emotional resonance of the moment. In my opinion, this can hardly be consciously created, but you can get rid of things that might stand in the way of making this feeling an impossibility – elements such as stress, the busy hectic nature of work at times, lack of concentration, permanent distractions. Also the feeling of standing before an obstacle that is difficult to overcome, experiencing tension and the fear of failing. But once the obstacle is overcome, the chances of “magic moments” increase. To quote Hölderlin: “And when the test… has passed through the knees… one may feel the forest cry.”

What or who inspires you in everyday life?

Recently I was walking through the streets of a city and through the window of a grey house in front of an old crocheted white curtain, I caught sight of a piece of paper that someone had printed out and stuck to the window. It said: “Multiply beauty!”. Beauty in itself is a value. Surprises, impulses, are other values for me. I like reading, listening to music and seeing a lot of theatre. I like to learn, to engage in science and history. I am happy when I gain new insights. Conversations with my partner, with friends, with artists, and with my colleagues are all very important for me.

There are “magic moments” when everything seems to fit. Moments that fulfil, inspire and give strength. Moments that confirm that the effort is worthwhile and that what you do is meaningful and valuable. Have you already experienced such moments in relation to your own activities?

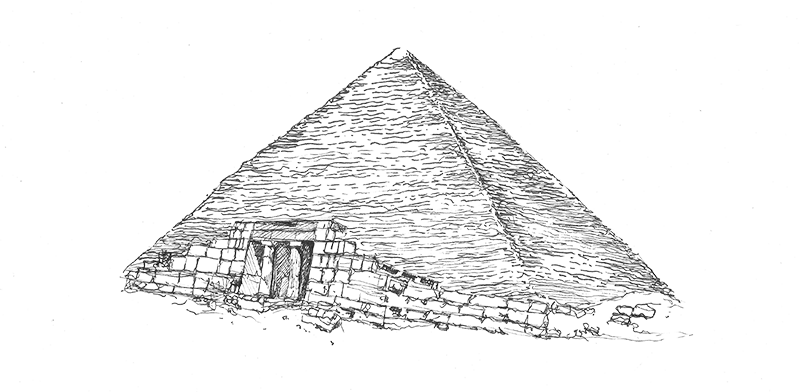

These special moments often occur in contexts beyond your own professional activities. Some months ago I was in Cairo and had the opportunity to visit the Pyramid of Khufu, which had been a childhood dream of mine. It was around Christmas time and Giza was full of tourists. The tickets for the pyramid are limited, so I made sure I got there early to get a ticket. Then I went inside the pyramid, in front of me were a group of Americans, behind me a group of East Asians. The stairs in the pyramid in front of the Great Gallery are very narrow, it was hot and the air was very stuffy. The people coming from the opposite direction pushed past the people climbing up. With doyens of people conversing in this enclosed environment it was incredibly loud. The path at the bottom of the stairs led to the pharaoh´s burial chamber. The chamber was constructed with the finest, polished granite, without decoration, in a rectangular high room, where the underside of the four and a half thousand year-old sarcophagus stood. Here too, far too many words were being spoken much too loudly in an infinite number of languages. Then, all at once, all of the visitors were gone and no one followed in behind. The overseer looked at my partner and me and also silently withdrew, so that we were now able to be completely alone in this room for 10–15 minutes. Not a sound, nothing and nobody. It was magical.

But also nature can be infinitely magical. One moment that springs to mind was when I was in Kenya many decades ago, when I first looked out over the majestic Rift Valley to the horizon. It was gigantic and awe-inspiring. In cases like these, it has a lot to do with anticipation, the expectation of a moment you have planned for and the effort that went into making it happen. In other cases, there are moments that come without any advance notice. I go to the theatre, expect nothing special and suddenly the performance inspires you and takes you somewhere special. Wonderful.

Are there moments when you doubt what you are doing?

Nothing happens in the theatre without doubt. It’s in everything. In every actress, in every director, in every writer, in every dramaturge. Every artistic process is always fraught with doubt. Right up until the premiere. It’s the same with running a theatre. You are constantly asking yourself the question – will the programme and its projects succeed? In the artistic process, you must embrace the doubt, but not let yourself be consumed by it. In the end, there will always be fears that you have to face.

In retrospect, can you find something positive in difficult moments?

I see it as a mechanism, an extremely clever trick of our brain, that events always appear to us retrospectively as if something positive, some sense, could be made out in them. Someone rides a bicycle, is hit by a car, breaks his or her leg, has a cast put on, and he or she has to stay at home for weeks. This person begins to draw out of endless boredom and discovers a talent and a great joy in it, which he or she was not aware of until now. This person may think that it was the accident that made him or her discover drawing. Events are thus connected consecutively with each other through our brain. There is no sense hidden in the actual bicycle accident. This trick enables us humans to come to terms with the events of our own lives instead of constantly struggling with fate and the past. Belief in a fixed fate or divine providence has a similar effect, reconciling us to the adversities of life and giving meaning to our existence as it seems to follow a higher metaphysical plan.

A second very meaningful effect of the evolution of the brain is the forgetting or repressing of experiences. The great Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story once about someone who cannot forget anything in his life. This character has everything present at all times, every moment, every sensory impression, he can review his entire life at any moment. This naturally turns into a nightmare, because most negative experiences are forgotten or repressed, so that we don’t have to deal with them every day. It’s a vital survival strategy for us humans.

Is there anything you would do differently in retrospect?

Little on a large scale, much on a small scale.

Do you want to contribute to society with your activities?

As a theatre director I am deeply convinced that theatre, or art in general, contributes a great deal to society. A frequently asked question is: “Can theatre change the world?” If you say yes to this question, in our time you are often lumped together with utopians who are far removed from reality. Therefore, more often we hear a “No.” to this question, a “We want to offer the audience something beautiful.” or “We want to give the audience impulses, but changing the world is not really possible.”. For me there’s no contradiction at all. The world changes in the heads of every single person. Every impulse, every feeling changes people. And people change the world. So yes, I want to give impulses with the theatre, show something beautiful and contribute to the shaping of society.

How well can you live from what you do professionally?

I have a permanent job and can live from my profession.

Is there something that is particularly occupying you at the moment?

A lot, if we are talking here about issues of the current day. The emerging selfishness in the world. The ever widening gap between rich and poor within regions, states and the world in general. The wealth of individuals, which is sometimes greater than the economies of entire countries. Geoengineering, i.e. the attempt to reverse the changes that mankind has inflicted on planet Earth over the past centuries. The fatal triad of overpopulation, agricultural cultivation of the entire world and increasing mechanisation, which has led to climate change, mass extinction of species and large-scale interventions in the planet’s lithosphere. Also the possibilities of manipulating people and opinions on a large scale as a consequence of digitalization.

Is there something you would like to (increasingly) spend time on in the future?

With evolution – where does this force of life in every organism in the world come from? With the natural sciences and with the questions of the future: How will our world change in the future? How will people live in the future? What ethical problems will occupy them?

What are you most grateful for in life?

For the people in my family and my circle of friends and for the path I have been able to take in life so far.

Interview

Laura Hilti, June 2020

Illustrations

Stefani Andersen

Links

TAK Theater Liechtenstein

Credits

All photos: TAK Theater Liechtenstein

This interview is part of the project “Magic Moments” by Kunstverein Schichtwechsel, in which people are interviewed about their careers, activities and their magical as well as difficult moments.

Curated by Stefani Andersen and Laura Hilti, Kunstverein Schichtwechsel.

Supported by Kulturstiftung Liechtenstein and Stiftung Fürstl. Kommerzienrat Guido Feger.

>>> All interviews