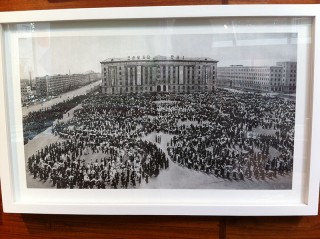

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the Korean Peninsula was divided in two. Within the polarizing global and state systems of the Cold War, a society and culture that had maintained a unified state entity for more than a millennium evolved radically divergent yet irrevocably interconnected economic, political, and ideological systems. The trauma of war and adversarial politics have too often sensationalized and over-simplified this condition, reproducing clichés and prejudices that obscure the complexity and possibilities that lie in the Peninsula’s past, present, and future. In the Korean Pavilion, the architecture of North and South Korea is presented as an agent—a mechanism for generating alternative narratives capable of perceiving both the everyday and the monumental in new ways.

The exhibition is inspired by “Crow’s Eye View,” a serial poem by the Korean architect-turned-poet Yi Sang (1910–37). Published in 1934 and influenced by the Dada movement, “Crow’s Eye View” is the emblem of the fragmented vision of a Korean poet who aspired to be a modern architect, an aspiration that was impossible to fulfill under the debilitations of Japanese colonial rule. In contrast to a bird’s-eye view—a singular and universalizing perspective—it points to the impossibility of a cohesive grasp of not only the architecture of a divided Korea but the idea of architecture itself. Ironically, while most of the world is relatively free to visit North Korea and South Korea, South Koreans are rarely given the opportunity for direct communication. Admittedly a South Korean point of view, Crow’s Eye View is a prologue for a yet unrealized joint exhibition of the two Koreas, what we would call the “First Architecture Exhibition of the Korean Peninsula.”

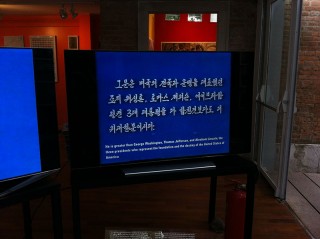

The exhibition is by no means a comprehensive or balanced presentation of the architecture of the two Koreas. Like uncharted patches of an irregular globe, a diverse range of work produced by architects, urbanists, poets and writers, artists, photographers and filmmakers, curators and collectors forms a multiple set of research programs, entry nodes, and points of view. They call attention to the urban and architectural phenomena of the planned and the informal, individual and collective, the heroic and the everyday. Intertwined yet in opposition, spilling over to each other, they reveal the way that a wide range of architectural interventions have reflected and shaped the life of the Korean Peninsula.