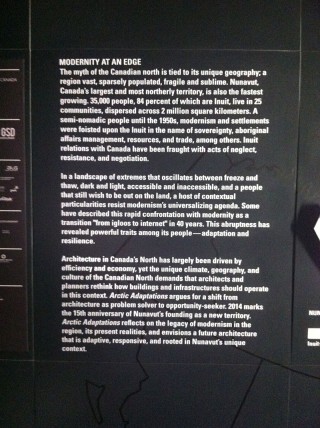

Modernity is typically unconcerned with the specificities of place, or even the premise of “the local.” Yet in a place with sometimes little to no daylight, temperatures averaging below freezing, no roads, and a people that live out on the land, modernity has been pushed to its limits. The climate, geography, and people of the Canadian Arctic challenge the viability of a universalizing modernity. A host of contextual particularities seems to resist modernism’s universalizing agenda. Following the age of exploration in the 20th century, modern architecture encroached on this remote and vast region of Canada, sometimes in the name of sovereignty, aboriginal affairs management, resources, or trade, among others. However, the Inuit have inhabited the Canadian Arctic for millennia as a traditionally semi-nomadic people. Inuit relations with Canada have been fraught with acts of neglect, resistance, and negotiation. Throughout the last 75 years, architecture, infrastructure, and settlements have been the tools for these acts. People have been re-located; trading posts, military infrastructure, and research stations have been built; even small settlements are now emerging as Arctic cities. Some have described this rapid confrontation with modernity as a transition “from igloos to internet” in 40 years. This abruptness has revealed powerful traits among its people—adaptation and resilience.

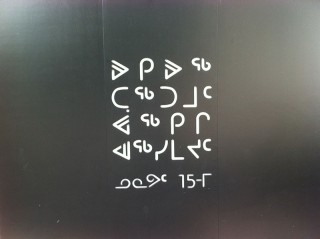

Nunavut and Nunavummiut

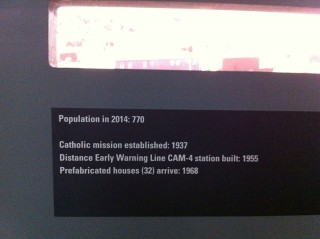

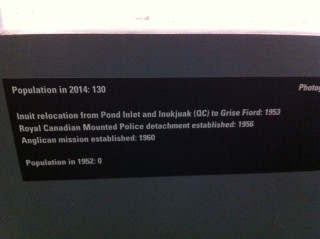

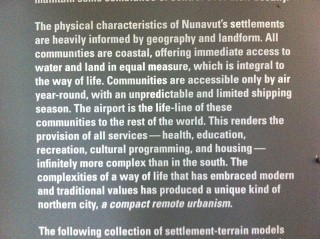

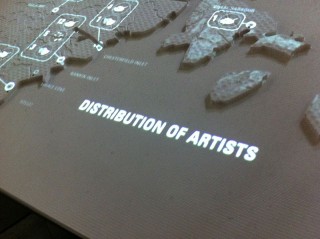

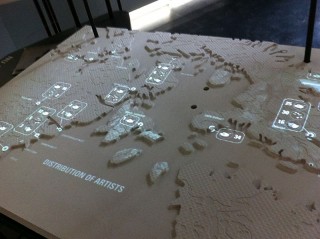

Nowhere is the trait of adaptation in the face of modernity better exemplified than Canada’s newest, largest, and most northerly territory: Nunavut. Nunavut, which means “our land,” was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999 following a land claims agreement established in 1993. Today, there are almost 33,000 people (Nunavummiut) living in 25 communities in Nunavut, across a massive two million square kilometres. Over 60% of the population is under the age of 25, making it a young, dynamic urbanizing nation. Communities range in population from 120 in the smallest hamlet to 7,000 in Iqaluit, Nunavut’s capital city. This region is above the tree line and has no highways connecting communities. The myth of the Canadian north is tied to its unique geography – vast, sparsely populated, fragile, and sublime. Yet Nunavut, like the entire Arctic region, is undergoing dramatic transformation as powerful climatic, social, and economic pressures rapidly collide.

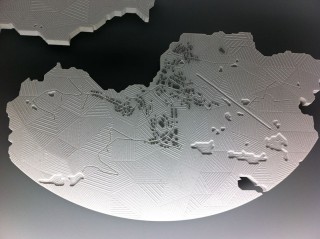

The unique climate, geography, and culture of the Canadian North offer the opportunity, indeed demands, that architects and planners rethink how buildings and infrastructures should operate. Faced with these challenges, architecture typically operates as a problem-solver, whereas Arctic Adaptations argues the possibility of architecture as an opportunity-seeker. In a landscape of extremes that oscillates between freeze and thaw, dark and light, accessible and inaccessible, Arctic Adaptations reflects on a difficult past, a challenging present, and envisions a future architecture that is adaptive, responsive, and rooted in Nunavut’s unique geography, climate, and culture.